Huelva: Ancient Civilizations and Natural Wonders of Southwestern Spain

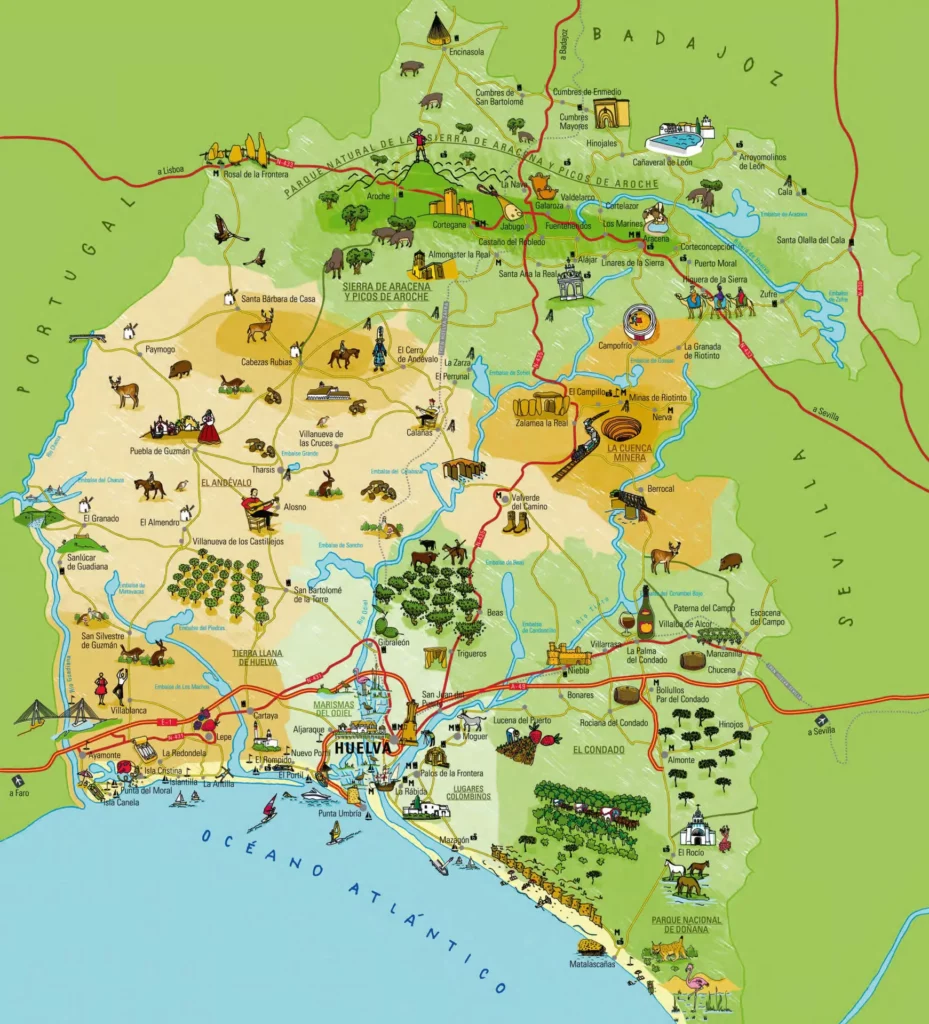

Nestled on Spain’s Atlantic coast at the far southwest of the Iberian Peninsula, Huelva’s landscapes have drawn humans for millennia. The rolling Sierra de Aracena to the north is laced with copper, silver, and gold veins, while the Odiel and Tinto rivers carve fertile plains toward the sea. Broad beaches and salt marshes—such as the Marismas del Odiel (a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve)—fringe the coast, providing natural harbors and rich fishing grounds. With over 3,000 hours of sunshine per year and a mild, wet winter climate, Huelva’s weather has long nurtured olives, vineyards, citrus orchards and salt flats. This sun-drenched, Atlantic-breezed environment not only yields famous local foods (like Jabugo Iberian ham and fresh strawberries) but laid the groundwork for the region’s deep agricultural and maritime heritage.

Prehistoric Huelva

Huelva also offers a window into prehistoric Europe. The “Matalascañas Trampled Surface” revealed the oldest hominin footprints in the region—dating back to 295,800 years ago, during the Middle Pleistocene. These rare marks, along with megafauna tracks and Mousterian tools, paint a vivid picture of early human and ecological activity

Huelva is a province rich in prehistoric monuments, with over 200 megalithic sites scattered across its landscape. Among these, the Dolmen de Soto, located near Trigueros, stands out as one of the most significant. Dating back to approximately 3000–2500 BC, it is one of the largest dolmens in the region and has been declared a National Monument. The dolmen features a long corridor leading to a burial chamber, constructed using large stone slabs, and is part of a larger megalithic complex that includes other burial sites and standing stones.

These megalithic structures not only serve as a testament to the architectural and engineering skills of ancient societies but also reflect the cultural and social dynamics of prehistoric Europe. The alignment and construction techniques of these monuments suggest a deep understanding of astronomy and a strong connection to the natural environment. The preservation and study of these sites continue to provide archaeologists with invaluable information about the beliefs and practices of early human societies in the Iberian Peninsula.

Biodiversity and Natural Heritage

The province enjoys over 3,000 hours of sunshine annually, with mild, wet winters and long, dry summers where average temperatures often reach 30°C (86°F) in July and August. This climate—tempered by Atlantic breezes—proved invaluable for viticulture, olive groves, citrus orchards, and salt production. As early as the Tartessian period, vines were cultivated here, and archaeological evidence suggests that Huelva may be the cradle of winemaking in the Iberian Peninsula. In Roman times, amphorae of Baetican wine, olive oil, and salted fish left Huelva’s shores for distant markets in Gaul, Britannia, and even the imperial city of Rome itself. The same combination of sun, soil, and sea that sustained these ancient industries continues to define Huelva’s agricultural wealth today, from world-renowned Jamón de Jabugo cured in the mountain air to the strawberries, oranges, and grapes exported worldwide.

The Jabugo ham and local seafood are world-famous, reflecting the rich ecosystem provided by the Doñana marshlands and the distinct microclimate of southern Iberia. The province of Huelva boasts an extraordinary biodiversity, shaped by its unique geographical location at the southwestern edge of the Iberian Peninsula and its diverse landscapes.

Among its natural jewels is the renowned Doñana National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Europe’s most important wetlands. This vast marshland ecosystem, encompassing marshes, dunes, forests, and rivers, serves as a critical refuge for an immense variety of flora and fauna. Doñana is especially vital as a migratory crossroads for millions of birds traveling between Europe and Africa, hosting species such as the endangered Spanish imperial eagle, the marbled duck, and the elusive Iberian lynx—the world’s rarest feline.

The park’s river systems, primarily the Odiel and Tinto, carve rich estuaries and salt marshes that create highly productive habitats. The interaction of fresh and saltwater generates unique saline environments that nurture halophytic plants and specialized aquatic species, contributing to the region’s agricultural richness. The salty, temperate climate with its mild winters and warm, dry summers provides ideal conditions for the cultivation of citrus fruits, vineyards, and olives—agriculture that has flourished here for millennia, tracing back to Tartessian and Roman times.

Moreover, the Marismas del Odiel (Odiel Marshes), a protected natural park adjacent to the city of Huelva, serves as an essential stopover for migratory birds and supports a complex food web sustaining fish, crustaceans, and shellfish vital to the local economy. The interplay between land and sea, salt and fresh water, creates an ecological mosaic that underpins both biodiversity and centuries-old human livelihoods.

This rich natural heritage has deeply influenced the culture and economy of Huelva. For example, the region’s wild horses, direct descendants of the ancient equine species brought to the Americas during the colonial period, still roam freely in Doñana, symbolizing a living link between Old and New Worlds. Likewise, the distinctive microclimate of Huelva has shaped unique gastronomic traditions, such as the production of the famous Iberian ham (jamón ibérico), whose flavor is intimately tied to the natural environment.

Furthermore, the agricultural knowledge and products from Huelva—such as the cultivation of grapes for winemaking, citrus fruits, and olives—were among the European staples transplanted to the Americas, shaping the continent’s agricultural landscapes and economies. The unique microclimate of the region, marked by warm temperatures and salty sea breezes, fostered the development of distinct crops like the Iberian ham (jamón ibérico), whose reputation has spread worldwide and now symbolizes the gastronomic excellence rooted in this land. The Condado de Huelva, now a prestigious DOP wine region, traces its viticultural roots to Tartessian times, when grape cultivation and wine-making were already practiced; archaeological evidence even includes amphorae and remnants of presses. The region’s wines—famously dubbed “Wines of the Discovery” for being among the first exporters to the Americas—prospered thanks to favorable soils and an Atlantic-moderated climate.

Ancient Civilizations

Nestled in the far southwest of the Iberian Peninsula, the province of Huelva—known in antiquity as Onvba Aestuarina—has stood for millennia at the meeting point of continents, cultures, and trade routes. Its earliest known golden age began with Tartessos (ca. 1200–500 BC), widely regarded as the first advanced civilization of Western Europe. Flourishing along the lower Guadalquivir and the Gulf of Cádiz, the Tartessians developed sophisticated metallurgy, smelting copper, silver, and gold from the mineral-rich Río Tinto and Tharsis mines. By the 9th century BC, their metalwork was already reaching Phoenician markets in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Greek sources such as Herodotus (5th century BC) described their legendary king Argantonios, whose reign reputedly lasted 80 years. These mineral exports did not merely enrich Tartessos; they underpinned a far-reaching trade network that supplied bronze to the Eastern Mediterranean and helped fuel the technological and economic rise of other ancient powers.

Following the decline of Tartessos around the late 6th century BC—possibly linked to shifting trade dynamics and Carthaginian expansion—the region came under the influence of Phoenician and later Carthaginian colonies along the Atlantic coast. When the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) brought Rome into Iberia, Onvba was absorbed into the Roman province of Hispania Ulterior, and later Baetica. Roman engineers expanded mining operations at Río Tinto on an unprecedented scale, producing tens of thousands of tons of ore annually. The wealth extracted here was so substantial that coins minted in Rome bore silver from Huelva’s earth, financing imperial campaigns and monumental building projects across the empire. In this way, the mineral heart of Huelva became an engine of the ancient world’s economy, linking a provincial corner of the Iberian Peninsula to the political and cultural epicenters of the Mediterranean.

The same sunny climate and productive land continued to sustain Roman exports of olive oil, salted fish and Garum, and barrels of sweet Baetican wine. Amphorae from Huelva have been found as far afield as Rome, Gaul, and Britannia, underscoring the city’s role in the Roman Empire’s trade network. The countryside’s legacy of viticulture also persisted: the Condado de Huelva region today traces its wine-making roots to those ancient times.

The Columbian Legacy

The province of Huelva, beyond its rich ancient history as the cradle of Tartessos and a key node in Roman and Phoenician trade networks, played a pivotal role in shaping global history through its direct connection to the Age of Discovery. Situated at the southwestern edge of continental Europe, its geographic position made it a natural gateway to the Atlantic Ocean, shaping its destiny as a launching point for voyages that forever altered the world map.

The port towns of Palos de la Frontera, Moguer, and La Rábida in Huelva’s province are famously linked to Christopher Columbus’s first expedition in 1492, which marked the beginning of sustained European contact with the Americas. These coastal hubs, steeped in maritime tradition and shipbuilding expertise dating back to the Roman and even Tartessian periods, provided the ships, crews, and logistical support that made transatlantic voyages possible. This expedition not only opened the gates to the New World but also facilitated the exchange of crops, animals, culture, and ideas in what became known as the Columbian Exchange—profoundly impacting societies on both sides of the Atlantic.

The legacy of these voyages lives on in Huelva’s cultural and ecological links to the Americas. Legendary “wild” horses still roam the Doñana marshes; these are descendants of Iberian horses taken to the New World by early explorers. Likewise, crops and techniques developed in Huelva – grapes for wine, olives, citrus and the cured Iberian ham (jamón ibérico) – were among the Old-World staples carried across the Atlantic to the Americas. In fact, 18th-century Huelva wines earned the nickname “Wines of the Discovery” for being among the first exports to the New World.

Huelva, the province where it all begins.

Huelva’s unique geography and rich history are thus intimately connected. The same rivers and winds that drew prehistoric hunters also bore the sails of Columbus’s caravels; the fertile soils that supported Neolithic farmers later grew the vineyards and olive groves exported around the ancient world. Today, travelers to Huelva can explore this tapestry of ancient civilizations and natural treasures, from dolmens and Roman ruins to bird-filled marshes. Whether one comes for archaeology, wildlife, or local gastronomy, Huelva offers an engaging journey through time where culture and nature converge.